Transforming Polarized Hostility into Cooperation, Part 1

A Summary of the Slow-moving Economic Hurricane that has Devastated Sections of the United States

Hi, everyone. I’m Mike Palmer. This is the first in a multi-part series of essays on Using Common Goals to Transform Polarized Hostility Into Mutually Beneficial Working Relationships in America. (Click here for Part II, What a Famous Social Psychology Experiment Can Teach Us About Overcoming Political Polarization in the United States.)

The purpose of part 1 is to understand some of what people in “America’s Heartland” have been going through over the past 30 to 40 years as deindustrialization, globalization, and automation have devastated their communities like a slow-moving hurricane. In it, I share some of what scholars have found and discuss the anger and resentment felt by working-class citizens.

The first step in resolving conflicts productively is for the parties to attempt to understand each other. This essay examines how these economic changes, combined with feelings of disrespect and betrayal by both political parties as well as coastal elites, have fostered deep political disaffection, contributing to the rise of populism and support for Donald Trump.

A Slow-moving Hurricane

Imagine an incredibly slow-moving hurricane sweeping across America’s Heartland—through the Midwest, the South, and the Southeast. But unlike natural disasters that destroy homes and claim lives in an instant, this hurricane inflicted a different kind of devastation. Over decades, factories shut down, jobs vanished, and once-thriving communities slowly crumbled. Storefronts were boarded up, businesses turned into tattoo parlors or bail bond offices, and the hum of industry gave way to an eerie silence. Those who could move away did, leaving behind a growing sense of despair and hopelessness. For the people living in the eye of this storm, the cause was not a force of nature but decisions made in distant corridors of power—decisions that prioritized financiers, corporations, and investors at the expense of working Americans. Trade agreements like NAFTA paved the way for manufacturers to relocate to Mexico, China, and Vietnam, leaving communities in ruins with no Federal Emergency Management Agency to come to their aid. To these Americans, it felt like their own government had abandoned them, and the sting of betrayal cut deep. If you were in their place, wouldn’t you feel the same?1

The American Midwest, once the heart of the nation’s industrial strength, has been suffering for decades. The factories that once employed thousands now stand silent, their windows shattered, the doors boarded up.

Once-thriving communities that built the cars, steel, and machinery that powered the nation are now filled with empty storefronts, crumbling schools, and people who feel as abandoned as the industries that left them behind.

The story of this economic decline is not just about numbers and policies; it’s about the people who have lived through it—their pain, their frustration, and their search for dignity in a world that seems to have forgotten them.

Take, for example, the story of Jim, a lifelong resident of Youngstown, Ohio, where the collapse of the steel industry devastated the local economy. Jim worked in the mills for over 30 years, following in his father’s footsteps. When the plant closed in 1992, Jim lost not only his job but the sense of identity and purpose that came with it. He had played by the rules—working hard, providing for his family, and being proud of the steel he helped create. But despite his loyalty, the company moved operations overseas, chasing cheaper labor. Jim found himself without work in a town where every job opening seemed to disappear as quickly as it came. Now in his sixties, Jim drives for Uber to make ends meet, but he still remembers the day the mill closed with a mixture of anger and heartbreak:

We built America. And they left us with nothing.

Jim’s story is not unique. Thousands of men and women like him across the Midwest have seen their livelihoods evaporate as industries moved abroad or replaced workers with machines. These aren’t just jobs that vanished—they were identities. They represented years of hard work, pride, and community. For many, like Jim, losing their job was more than a financial hardship; it was the loss of their place in society. They had done everything right, yet they were discarded like obsolete machinery.

Economic Decline and the Sense of Betrayal

The root of the Midwestern grievance lies in the dramatic economic transformations that have unfolded over the past 30 to 40 years. In cities like Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Flint, Michigan, industrial jobs were the lifeblood of communities. Workers without college degrees could secure stable, well-paying employment, allowing them to support their families, buy homes, and send their children to college. They were the backbone of America’s post-World War II prosperity.

But as deindustrialization took hold, globalization accelerated, and trade agreements like NAFTA facilitated the outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to countries with cheaper labor, the factories began to close. Between 1979 and 2000, U.S. manufacturing jobs declined by nearly 30%, a loss of around 5.5 million jobs, many of them in Midwestern states.2 Towns that once bustled with economic activity were reduced to shadows of their former selves. Factories became relics, slowly decaying along with the hope of those who once worked in them.

People like Jim and his neighbors were left to wonder: What happened to the American Dream? They felt promised that hard work would lead to success and stability. But instead, they found themselves betrayed by a system that seemed more interested in corporate profits and globalization than in the people who had built the foundation of the country’s prosperity.

This does not necessarily mean they are destitute. Thanks to the social safety net, many probably have enough money to subsist, if barely.3 But . . .

Humans Do Not Live by Bread Alone

Human beings are driven not just by the need for material sustenance but by a profound need for meaning. As Viktor Frankl famously argued in Man's Search for Meaning, "life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose." Frankl's work, rooted in his experiences as a Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, highlights the centrality of meaning in human life. Without a sense of purpose, individuals can experience feelings of despair, depression, and worthlessness, regardless of their material circumstances. Meaningful work provides a framework through which people understand their contribution to society and their personal growth. It offers a sense of direction and significance, anchoring individuals within a broader social and moral order.

Research in psychology supports this understanding. Studies by Michael Steger and colleagues using the Meaning in Life Questionnaire emphasize that individuals who find meaning in their work and personal lives report higher levels of psychological well-being and resilience. The classic study on The Motivation to Work by Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman found that achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility, and advancement—all factors that contribute to a sense of meaning—were more important than salary in job satisfaction and motivation.4

Conversely, when people lose the ability to engage in meaningful work—whether through unemployment, underemployment, or alienation—they are more likely to experience depression and anxiety. In the context of economic decline in the Midwest, the loss of meaningful work has not only led to financial hardship but also to a widespread sense of purposelessness, contributing to the feelings of anger and resentment that many now direct at the political and economic elites.

Meaning, then, is not a luxury but a mental and emotional necessity, one that sustains the spirit as much as bread sustains the body.

The Emotional Response: Victimization and Resentment

The economic collapse that swept through the Midwest brought more than just financial ruin. It shattered the emotional and psychological well-being of countless individuals and families. For many, the loss of a job wasn’t just a loss of income; it was a profound blow to their sense of self-worth. As Dale Miller describes in Disrespect and the Experience of Injustice, being treated unfairly or disrespected can be as psychologically damaging as material deprivation. Many Midwestern workers have experienced such disrespect as well. They had played by the rules, yet they were excluded from the benefits of the new global economy.

Another example comes from Susan, a single mother in Dayton, Ohio, whose job at an auto-parts manufacturer disappeared when the company relocated to Mexico. Susan had been with the company for 18 years. She had built a life around that job—bought a modest home, enrolled her kids in school, and made plans for the future. But all of that was ripped away when the factory shut down.

“I gave everything to that job,” she says. “But when they packed up and left, they didn’t even say goodbye. It’s like we never mattered.”

For people like Susan, the anger and resentment aren’t just about the loss of a paycheck. It’s about the feeling that they’ve been discarded—that their work, their dedication, and their contributions didn’t count. They feel like victims of a system that values profits over people, and that feeling of betrayal is deeply personal.

The Perception of Coastal Elites and Political Alienation

The sense of betrayal is compounded by the perception that the political and cultural elites—often based in coastal cities—are dismissive of their struggles. Many Midwesterners feel that both major political parties have abandoned them. Democrats, once the party of the working class, are now seen by many in these communities as a party of urban, educated elites more focused on environmental issues and global cooperation than on the bread-and-butter concerns of American workers. The passage of NAFTA under President Bill Clinton is often cited as a key moment in this perceived betrayal, as it opened the floodgates to outsourcing and the hollowing out of American manufacturing.5

Meanwhile, the Republican Party, long aligned with free-market policies and corporate interests, also lost favor among many working-class Midwesterners. The GOP’s support for trade liberalization, deregulation, and tax cuts for the wealthy left many feeling that both parties were more interested in serving the interests of Wall Street and Silicon Valley than in protecting the jobs and livelihoods of ordinary Americans.

The alienation from political elites was only deepened by cultural dismissiveness. Hillary Clinton’s infamous reference to Trump supporters as a “basket of deplorables” during the 2016 election became a symbol of the perceived condescension with which many in the working class felt they were regarded. For people like Jim and Susan, this was more than just a political gaffe—it was a confirmation that the elites in Washington and New York viewed them as backward, uneducated, and morally inferior. They were being ignored, and when they were noticed, it was with an air of superiority.

This sense of disrespect is pervasive. It’s not just that they feel left out of the economic benefits of globalization; it’s that they feel actively disrespected by the political, economic, and cultural elite. This disrespect fuels resentment and anger, making many open to political figures who promise to challenge the status quo and give voice to their grievances.

Could Those Who Focus Largely on Economics Be Getting it Wrong?

In 2004, What’s the Matter with Kansas? created quite a stir. In it, Historian Thomas Frank explores the seeming paradox of working-class Americans in Kansas voting against their economic interests by supporting conservative politicians who prioritize culture wars over economic issues. Frank argues that the Republican Party has successfully shifted the focus from economic policies that benefit the wealthy to social and cultural issues like abortion and gun rights, thereby galvanizing rural voters while neglecting their economic needs.

But to several scholars who grew up in the region, Frank’s argument did not ring true. In The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker, for example, Katherine Cramer examines the rise of populist politics in Wisconsin through the lens of "rural consciousness"—a sense of identity and perceived injustice among rural voters who feel ignored and disrespected by urban elites. Cramer argues that this rural consciousness fueled resentment toward government and drove support for Scott Walker’s conservative policies, as rural voters believed that their economic and social concerns were overlooked by politicians who favored urban areas.

In his 2021 dissertation, Unhealthy Democracy: How Partisan Politics is Killing Rural America, Michael Shepherd argues that rural America’s health and economic challenges are exacerbated by partisan politics. Despite facing severe health disparities and economic decline, cultural grievances, racial attitudes, and partisanship often lead rural voters to align with the Republican Party’s anti-government stance, even though government policies could help address their struggles.6

In The Rural Voter: The Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America, Nicholas Jacobs and Daniel Shea argue that the political attitudes of rural voters are shaped by a deep sense of place and cultural identity, which leads to distinct political behaviors and grievances. The authors suggest that rural voters feel alienated from urban and coastal elites, perceiving government policies as favoring cities over rural areas, thereby fueling a growing political divide in America. They emphasize how these regional and cultural divides are contributing to the broader polarization in the U.S.

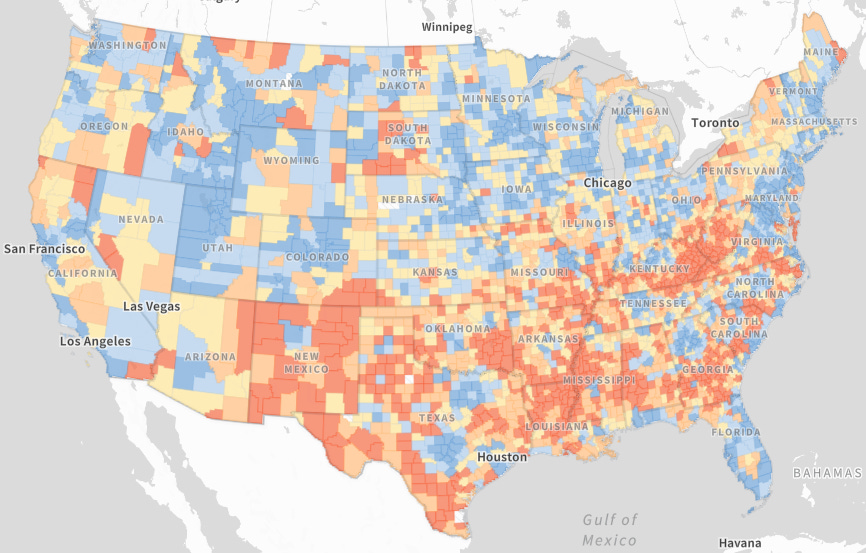

The Map of Distressed Communities

According to the Economic Innovation Group, almost 54 million people (15.6% of the US population) live in distressed communities. Another 66 million (19.2%) live in places at risk of becoming a distressed community. That’s roughly 35% of the US population (120 million people) that lives in distress or near distress.

The Economic Innovation Group uses 7 components to measure distress and risk of becoming distressed:

No high school diploma: Share of the 25 and older population without a high school diploma or equivalent.

Housing vacancy rate: Share of habitable housing that is unoccupied, excluding properties that are for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use.

Adults not working: Share of the prime-age (25-54) population that is not currently employed.

Poverty rate: Share of the population below the poverty line.

Median income ratio: Median household income as a share of metro area median household income (or state, for non-metro areas and all congressional districts).

Changes in employment: Percent change in the number of jobs over the past five years.

Changes in establishments: Percent change in the number of business establishments over the past five years.

As you can see from the map, while every state has some distressed communities (red color), the greatest concentration is in the Midwest, South, and Southeast.

These people are hurting. The American Dream seems out of reach to most.

The Rise of Populism: Donald Trump and the Tea Party

A deep well of resentment and anger set the stage for the rise of populism in the form of the Tea Party and later Donald Trump. Trump’s rhetoric about “draining the swamp” in Washington, renegotiating trade deals, and imposing tariffs on foreign goods resonated deeply with voters who felt abandoned by both parties. His blunt, unapologetic attacks on NAFTA, immigration, and the political establishment gave voice to the frustrations of those who felt that neither Democrats nor Republicans cared about their struggles.

Trump’s promise to bring jobs back to America, his attacks on global elites, and his willingness to stand up to the media all reinforced the idea that he was fighting for the “forgotten men and women” of America. For many, supporting Trump wasn’t just about policy—it was about reclaiming their dignity, pushing back against a system that had ignored or disrespected them for far too long.7

In places like Youngstown and Dayton, where factories had closed and opportunities dried up, Trump’s message struck a chord. Here was someone who, unlike the polished politicians of Washington, seemed to understand their pain, their anger, and their desire for respect. Trump’s populism, much like the Tea Party before him, provided a vehicle for expressing the rage that had been building for decades.

That Trump has no intention of delivering on his grandiose promises—”We’ll build a wall and Mexico will pay for it”—makes his demagoguery all that more tragic for his victims. His is the false hope of the consummate con man who tricks his mark into believing the highly improbable. At one rally, he slipped up and admitted: “I don’t care about you. I just want your vote.”

Summary: The Roots of Political Disaffection

The economic decline of the Midwest has had profound emotional and psychological consequences. For many working-class citizens, the loss of manufacturing jobs has not only brought financial hardship but also a deep sense of disrespect and injustice. They feel like they played by the rules and yet were left behind, victims of a system that prioritized corporate profits and global markets over their well-being.

The anger and resentment that has taken root in the Midwest is not just about policy; it is about the feeling of being discarded and disrespected by the political and cultural elites. This discontent has fueled the rise of populism and made many more inclined to support figures like Donald Trump, who promise to disrupt the status quo and give voice to their grievances. Until these emotional needs for respect, acceptance, and meaning are addressed, the deep divisions in American politics will continue to fester.

Coming Up in Part 2

Thanks for reading/listening to Using Common Goals to Transform Polar Hostility in America, Part 1. In Part 2, I will share what social psychologists have learned about transforming conflict between groups from hostility to harmony using superordinate goals.

The mission of Becoming Neighbors for Good is to help subscribers contribute to making the United States “a More Perfect Union” by working with others to advance the common good. If you’re not yet a subscriber, please join us on the journey.

I’m Mike Palmer.

(Click here for Part II, What a Famous Social Psychology Experiment Can Teach Us About Overcoming Political Polarization in the United States.)

This story is told in much greater detail by several books and articles. See, e.g., Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (The New Press, 2018); Justin Gest, The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality (Oxford University Press 2016) (focuses on the UK but tells a similar story); David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” 103 American Economic Review 2121 (2013); Robert E. Scott, “Heading South: U.S.-Mexico Trade and Job Displacement After NAFTA,” Economic Policy Institute (2011); Paul Krugman, “Trade and Wages, Reconsidered,” 2008 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 103-154 (2008).

See Josh Bivens, “Shifting blame for manufacturing job losses: Automation, trade, and outsourcing,” Economic Policy Institute (2004); Eduardo Porter, “The Hard Truth About Trying to Save the Rural Economy,” New York Times (December 2018); Rachel L. Harris and Lisa Tarchak, “Small-town America is Dying: How Can We Save It,” New York Times (December 22, 2018)

According to “The Great Trans-fermation,” a study published by Economic Innovation Group, as of 2022, income from government transfers constitutes 25% or more of all personal income in 53% of the counties in the country.

See also Dave Ulrich and Wendy Ulrich, The Why of Work: How Great Leaderes Build Abundant Organizations That Win (McGraw-Hill, 2010); Joel Kurtzman, Common Purpose: How Great Leaders Get Organizations to Achieve the Extraordinary (Jossey-Bass, 2010); Richard Elsworth, Leading with Purpose: The New Realities (Stanford Business Books, 2002)

See, e.g., Robert E. Scott, “Heading South: U.S.-Mexico trade and job displacement after NAFTA,” Economic Policy Institute (2011).

In April 2024, Nicholas Jacobs published a lengthy article in Politico with the title, “What Liberals Get Wrong About ‘White Rural Rage’ — Almost Everything,” in which he presents a detailed analysis of White Rural Rage, arguing that the authors completely misunderstand rural America. In a Newsweek article, Kristin Lunz Trujillo similarly argues that “White Rural Rage Cites My Research. It Gets Everything About Rural America Wrong.” See also Emma Goldberg, “How ‘Rural Studies’ Is Thinking About the Heartland,” New York Times (June 29, 2024).

This strategy proved successful, as Trump won key swing states in the Midwest, including Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, where the economic pain of deindustrialization had been most acute. A study from the Pew Research Center found that Trump performed significantly better than previous Republican candidates among white, non-college-educated voters, particularly in these states. See Pew Research Center, “An examination of the 2016 electorate, based on validated voters” (August, 2019).