Project 2025's Roots in White Christian Nationalism, Part 1

Project 2025 in the Context of Patriarchy in Anglo-American History and Culture

Hello, everyone. I’m Mike Palmer. This is Part 1 of Chapter 1 of Project 2025 Explained. The book is designed to briefly and comprehensively present what Project 2025 is and what it would mean for our democracy and Constitutional order if put into practice. This first part of Chapter 1 sets the stage by summarizing the roots of White Christian Nationalism in Anglo-American Patriarchy. In Part 2 of Chapter 1, I summarize the history and role of patriarchal rule, slavery, and racism in White Christian Nationalism. In Part 3, I briefly speak to the role of patriarchal rule and misogyny in White Christian Nationalism. Having this historical and ideological context will help us better understand the overarching, long-term agenda of Project 2025. Please leave comments and suggestions and share the essays with others.1

Roots of White Christian Nationalism in Anglo-American Patriarchy and Its Expression in Mandate for Leadership

White Christian Nationalism in the United States is deeply rooted in the historical framework of Anglo-American patriarchy, a system of social organization that has profoundly shaped the legal, political, and cultural landscape of the nation. This patriarchal foundation is central to understanding how White Christian Nationalism evolved and how it is expressed in contemporary political documents like Mandate for Leadership, a comprehensive policy agenda associated with the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025.

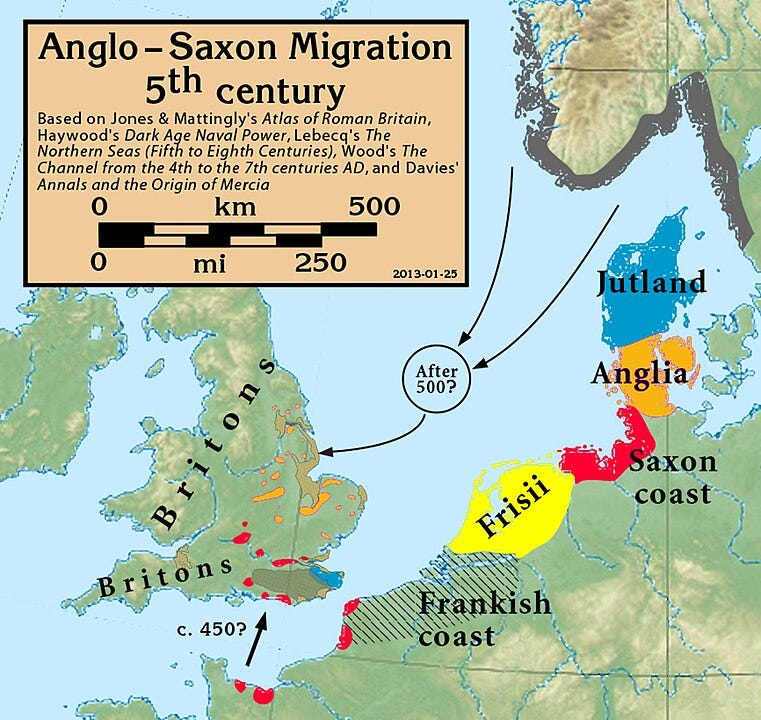

The story begins with the departure of the Romans from Britain in 410 CE, leaving behind a land predominantly inhabited by Celtic tribes. Over the next several centuries, these Celts faced invasions and settlements by the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and other Germanic tribes from what is now the coasts of Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands. (See Anglo-Saxons.)

Settling in small villages initially, the invaders used the Roman pater familias model as the basic form of governance both within expanded families and in communities. (See Anglo-Saxon Settlements.)

Under Roman law, the pater familias—the male head of the household—held absolute authority and power over all family members, including property rights and legal responsibility.

The invaders eventually established new kingdoms and developed governance structures that were deeply influenced by the Roman concept of pater familias.

As these new kingdoms in England took shape, the pater familias model was adapted into broader forms of governance, where kings exercised authority over their subjects akin to that of a patriarch over an extended family. This patriarchal structure became a cornerstone of English governance, with power centralized in the figure of the king, who was seen as the father of the nation.

The Christian Church played a significant role in reinforcing this patriarchal system. Although Church governance operated separately from the monarchy, it often supported and was supported by the ruling class, reinforcing traditional gender roles and the authority of male leaders both in the home and in society.

During the 8th and 9th centuries, English kings began codifying laws, often focusing on compensatory justice, where specific monetary values were assigned to different harms.2 The king’s authority was largely unquestioned, and his decrees were the law of the land.

However, the idea that even kings should be subject to certain laws began to take hold with the Charter of Liberties in 1100, which King Henry I of England issued under pressure from his nobles.

This document limited the king’s power and laid the groundwork for the idea that rulers should be bound by law—a concept that would evolve into the Rule of Law.

The tension between the patriarchal model of governance and the emerging concept of the Rule of Law continues throughout Anglo-American history to the present. Key milestones include the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, which established the principle that the king was not above the law; the development of the English Parliament and its legislative authority; the Declaration of Independence in 1776, which articulated a vision of governance based on individual rights; and the U.S. Constitution of 1787, which established a framework for a government based on the separation of powers and the protection of civil liberties.

Despite these developments, patriarchy has rarely ceded power without resistance. Throughout history, dominant male figures have often viewed patriarchy as convenient, efficient, and personally rewarding, with women, children, and subordinates expected to comply with the patriarch's commands. The ideologies that developed to justify patriarchy in both family and government settings often framed it—and continue to do so today—as necessary for social stability and the preservation of religious and moral values. Project 2025’s Mandate for Leadership can be seen as a contemporary expression of this patriarchal view.

Anglo-American Patriarchy and the Concept of Authority

The foundations of White Christian Nationalism are closely tied to the concept of patriarchal authority that has been a defining feature of Anglo-American governance since the colonial era. As Markus Dirk Dubber explores in The Police Power: Patriarchy and the Foundations of American Government (2005), the early American legal and political systems were heavily influenced by the model of the patriarchal household, where the father exercised absolute control over his family. This model was then extrapolated to the state, with the government assuming the role of the patriarch, tasked with maintaining social order and moral authority.

This patriarchal structure was not just a feature of domestic life but was embedded in the broader political and legal frameworks of the Anglo-American world. The state’s police power—the authority to regulate behavior and enforce social norms—was fundamentally rooted in this patriarchal notion of control. In this framework, the state, like the patriarchal father, was responsible for the protection and moral guidance of its citizens, who were viewed as dependents in need of oversight.

Dubber’s analysis highlights how this model of governance relied on a coercive power dynamic, where authority was maintained through control and subordination. This patriarchal authority extended beyond the family to encompass broader societal relations, including those between races, genders, and social classes. In this context, White Christian Nationalism can be seen as an extension of this patriarchal order, where authority is justified by religious doctrine and enforced through social and legal mechanisms.

Patriarchy, Religion, and the Foundation of White Christian Nationalism

The religious justification for patriarchal authority is a central theme in the development of White Christian Nationalism. The intertwining of patriarchal and religious values created a potent ideological framework that supported the subordination of women, the maintenance of racial hierarchies, and the control of moral behavior. Biblical passages, particularly from the Pauline epistles, were frequently cited to support the notion of male authority and female subordination, reinforcing the idea that social order depended on strict adherence to traditional gender roles and family structures.

This religiously infused patriarchy also extended to racial relations, where White supremacy was often justified through a combination of biblical interpretation and pseudo-scientific theories. The patriarchal model of authority thus became a way to maintain not only gendered but also racial hierarchies, with White Christian men positioned as the ultimate arbiters of moral and social order.

The Expression of Patriarchal Authority in Mandate for Leadership

The Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership, a key policy document for Project 2025, reflects the enduring influence of this patriarchal framework within the ideology of White Christian Nationalism. The Mandate lays out a vision for governance that emphasizes the restoration of traditional values, the reinforcement of social hierarchies, and the exercise of strong state authority—all hallmarks of the patriarchal order described by Dubber.

The document advocates for policies that seek to reassert control over areas of life traditionally governed by patriarchal authority, including family structure, education, and reproductive rights. For example, the Mandate emphasizes the need to protect the traditional family unit, defined in terms that reinforce male authority and female subordination. It also advocates for the restriction of abortion rights, reflecting the patriarchal desire to control women’s reproductive choices and maintain traditional gender roles.

Moreover, the Mandate expresses a broader desire to reinforce social order through the exercise of state power, much like the police power described by Dubber. This includes a call for stricter law enforcement, the expulsion of undocumented immigrants, and the defense of religious freedom—often framed as the right to legally impose Christian values in public life, for example, by posting the 10 Commandments in every classroom. These policies are presented as necessary for the preservation of social stability and moral order, echoing the patriarchal themes that have historically underpinned American governance.

The Continuing Legacy of Patriarchal Authority

The patriarchal roots of White Christian Nationalism and their expression in contemporary policy documents like Mandate for Leadership demonstrate the enduring influence of this framework in American political life. The vision of governance articulated in these documents reflects a desire to return to a supposed golden age of social order, where traditional hierarchies of gender, race, and religion were firmly in place and enforced by a strong, paternalistic state.

This legacy of patriarchal authority continues to shape the political and cultural landscape of the United States, influencing not only policy decisions but also the broader social attitudes that support White Christian Nationalism. Understanding the historical roots of this ideology in Anglo-American patriarchy is crucial for analyzing its current manifestations and the implications of its resurgence in American politics.

Much of the summary in this essay is based on the following authorities:

Markus Dirk Dubber, The Police Power: Patriarchy and the Foundations of American Government (Columbia University Press, 2005) Dubber’s book offers a comprehensive analysis of the historical and conceptual connections between patriarchal authority and the development of police power in American governance, tracing these ideas back to their Anglo-American roots.

Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract (Stanford University Press, 1988). Pateman explores the historical development of patriarchy, particularly in the context of social contract theory, and its implications for understanding modern political structures.

Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (Yale University Press, 1992). Colley provides an in-depth look at the formation of British national identity, including the role of patriarchal structures in shaping political and social life.

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England (MacMillan, 1883). Stephen’s historical work offers insights into the development of English law, including the role of patriarchal authority in shaping legal principles and practices.

Pauline Stafford, Queens, Concubines, and Dowagers: The King's Wife in the Early Middle Ages (University of Georgia Press, 1983). Stafford examines the role of women in early medieval governance, highlighting the patriarchal structures that governed both public and private life.

Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (Columbia University Press, 1988). Scott’s work discusses the historical intersections of gender and power, providing a framework for understanding the persistent influence of patriarchy in Western political thought.

John A. Garraty and Peter Gay, The Columbia History of the World (Harper & Row, 1972). This historical overview includes discussions of the Roman Empire, early Anglo-Saxon England, and the development of English common law, providing context for the emergence of patriarchal governance.

Sir Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (Cambridge University Press, 1968, orig. 1895). Pollock & Maitland continues to be the go-to starting point for English legal history.

Albert Venn Dicey, Introduction to the Law of the Constitution (8th ed., MacMillan, 1915, orig., 1885). Dicey introduced the term “Rule of Law” in an extensive discussion in Part II of this book. He continues to be a source of wisdom on the subject.

Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America (Simon & Schuster, 2017). FitzGerald provides a comprehensive history of the evangelical movement in America, documenting its political rise and influence, which is critical for understanding the religious and political forces driving White Christian Nationalism and informing Project 2025’s agenda.

The most famous law code of this type was the Domboc issued in the late 880’s to 890’s by Alfred the Great. See Todd Preston, King Alfred’s Book of Laws: A Study of the Domboc and Its Influence on English Identity (MacFarland, 2012). Alfred’s Domboc also relied on and incorporated significant parts of the Law of Moses, including the 10 Commandments. Id. at 7.

Good look here at the roots of patriarchy. It goes back a very long way.